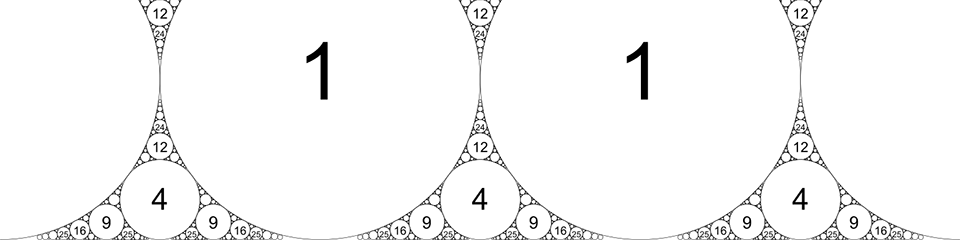

Problem 199 is focused on packing in as many circles as possible into a larger circle and determining the remaining area that has not been filled in. After three initial circles have been placed, the question is what is the fraction of the area remaining after 10 iterations of further circle packing. The figure below shows an image with 3 iterations of circles placed after the initial 3 circles.

In this scenario, to determine the curvature—and thus the radius—of the fourth circle, given three, we are going to make use of Descartes’ theorem. What we are essentially building is an Apollonian gasket, a circle based fractal pattern. Descartes’ theorem defines the relationship of the curvature, k0, of one circle with the other three as follows:

with the \(\pm\) reflecting that there are two solutions, one outside the given three circles, and one inside. We can use this formula initially to form a relationship between the three starting circles of equal size and the larger circle that they sit in. To keep it simple, we will assume that the three circles have a radius of 1. To do this, we use the formula above, but with a negative sign as we want the circle on the outside of these three.

k1 = k2 = k3 = 1

outer = k1 + k2 + k3 - 2*np.sqrt(k1*k2 + k2*k3 + k1*k3)

r0 = - 1 / outerFrom here, we basically have to fit a circle into each open space, which would generate three smaller spaces, then fit a circle into these spaces, and so on. Given that this is a repetitive process that we are implementing, a recursive function is needed. Whenever we split a space up by adding a circle, the three new spaces each have two of the previous circles and then the new circle bounding them. We can then use these to figure out the curvature of the next circle to add and so on. Putting all of this together, and adding the square root component (because we want to put in the interior circles) gives us the following function:

def recursive_get_apollonian_k(k1,k2,k3,curr_depth,final_depth):

k0 = k1 + k2 + k3 + 2*np.sqrt(k1*k2 + k2*k3 + k1*k3)

global k_arr

k_arr = np.append(k_arr, k0)

if curr_depth < final_depth:

curr_depth += 1

new_k = recursive_get_apollonian_k(k0,k1,k2,curr_depth,final_depth)

new_k = recursive_get_apollonian_k(k0,k1,k3,curr_depth,final_depth)

new_k = recursive_get_apollonian_k(k0,k2,k3,curr_depth,final_depth)In this function, we have added curr_depth and final_depth as parameters so that we can determine how far down the rabbit hole we want to go. In this case, we will set final_depth to 10. With this function defined, we want to run through it a total of four times, once for each of the different regions. In each iteration we will take note of the new curvatures calculated and add them to the an array, k_arr. I have done that in the following code snippet. It’s also worth noting here that three of the starting spaces are identical (the ones around the outside), so we could do one of these and triplicate the results. However, it doesn’t take long to just run through three times.

k_arr = np.array([1,1,1])

for i in range(3):

recursive_get_apollonian_k(1,1,outer,1,10)

recursive_get_apollonian_k(1,1,1,1,10)From here, we can simply compute and compare the area of the original circle with the summation of the area of the packed circles to determine how much space is left!

orig_area = np.pi * r0**2

k_to_area = lambda x: np.pi * (1/x)**2

taken_area = k_to_area(k_arr)

taken_area = np.sum(taken_area)

spare = 1 - (taken_area) / orig_area

print(f"Spare area as percentage: {spare:0.8f}")What I particularly enjoyed when working through this problem, and researching more afterwards, was the reminder of how inter-connected seemingly abstract topics can be. This circle based fractal pattern is an interesting pattern to play with and has many interesting mathematical properties (Elena Fuchs wrote a thesis on it here for the very interested reader), but also some interesting properties related to random packing, with physical applications related to bubbles and trees (source: American Scientist). And as with most interesting mathematical concepts, they are represented in the arts, in this instance, a poem by Frederick Soddy. An unwritten rule when communicating about this fractal pattern seems to be mentioning this poem, so I will finish with it. Enjoy! :)

The Kiss Precise

For pairs of lips to kiss maybe

Involves no trigonometry.

’Tis not so when four circles kiss

Each one the other three.

To bring this off the four must be

As three in one or one in three.

If one in three, beyond a doubt

Each gets three kisses from without.

If three in one, then is that one

Thrice kissed internally.

Four circles to the kissing come.

The smaller are the benter.

The bend is just the inverse of

The distance from the center.

Though their intrigue left Euclid dumb

There’s now no need for rule of thumb.

Since zero bend’s a dead straight line

And concave bends have minus sign,

The sum of the squares of all four bends

Is half the square of their sum.

To spy out spherical affairs

An oscular surveyor

Might find the task laborious,

The sphere is much the gayer,

And now besides the pair of pairs

A fifth sphere in the kissing shares.

Yet, signs and zero as before,

For each to kiss the other four

The square of the sum of all five bends

Is thrice the sum of their squares.

– Frederick Soddy, 1936

Opening banner image by: Nilesj - Own work, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=70324627